| |

next

April 15th, 2009

The basic problem, I believe, is that people forget that money is an abstraction. The “real” economy is making things; money is just a mechanism for the allocation of effort. The fundamental problem is far too much of our effort got allocated to the task of manipulating this abstraction in order to siphon off a rake while not contributing themselves anything of real value to the economy as a whole. This is just a fundamental drag on the economy.

In some sense we’re all hostages to this system, and I think it’s obvious the system needs to be dismantled. However, causing a panic in the market (which would happen if a major bank defaulted on its obligations, which I am quite certain would cause a massive and immediate series of cascading defaults) would stop the abstraction (money) from moving around nearly entirely, which would then stop actual production from occurring, leading to real damage which would take years to repair.

That’s why I am not upset at Geithner and Obama for saying, we can’t afford that. Even if your goal is to dismantle the system and recreate it, which I share with Galbraith and others, I believe that we need to find a way to do that which doesn’t cause real production to halt. Keep in mind that our circumstances differ this time: when FDR came to office unemployment was 25%. Now, it is below 10%. We have a little more breathing room.

I believe it will take time and delicacy to both dismantle the system as it exists today and not cause real production to come to a grinding halt, which would take years to recover from. It will take months to design and implement such changes. For example, one radical option might be to simply abrogate all credit default swap contracts, and then make most of them illegal. All the banks have these big guns pointed at each other — the CDSes, yet what if they all cancel each other out? Even if they do, if one of them defaults then they all default, in a cascade, but if they all “default” at once by government fiat? The problem is, many of these are international contracts so the US would have to act in concert with foreign governments, which is very likely impossible.

Another option is to simply make most of these instruments illegal going forward (particularly the totally synthetic CDSes, the ones not based on any underlying ownership of collateral) and move to gradually take them off the balance books of the banks. The irony of all this is that, high as foreclosure rates are today, they still represent a tiny fraction of the total number of outstanding mortgages. The reason this tiny fraction has created a total destabilization of the world economy is that the rules allowed the bankers to essentially multiply the risk by orders of magnitude through complex securitization that I believe even they didn’t understand, so even a small drop in housing value caused the entire market to come crashing down.

The end result needs to be getting rid of most of the gambling sector of the financial services economy, which is a drain not only on money but on talent and intelligence. However, I agree with Geithner’s instinct not to let this crisis spill over into the real economy at a rate even higher than it has so far, to give us time to dismantle the fantasy economy. I am not sure yet whether he and Obama have a plan that will dismantle enough of the fantasy economy as we need, but, I do believe both of them understand the need for something along these lines — it’s been something Obama has explicitly raised in a number of his speeches and also something Geithner has talked about in public, including his most recent public appearances.

There is a crisis in the real economy as well, insofar as we have a lot of industries (the auto industry, for instances) with outdated management practices, bad product design, undereducated and undertrained workers, etc. On the other hand, we also have some industries (tech) which remain far ahead of the rest of the world, and while our educational system is crap, we still have the best universities in the world, etc. All in all, a mixed bag.

But I believe the main reason for this came from the financialization of the economy. That is to say, more and more resources were siphoned off the top by the financial manipulators, which means less was available for investment in real innovation, research, development, training, education, and so forth. It also siphoned off the “worst and brightest” into the financial services sector, a brain drain into a largely unproductive sector of the economy. I say largely because I believe venture capital is an exception — they’re investing in the real economy, directly, which is generally quite salutary and something we ought to continue to support. As for most of the the rest of the financial services industry, it’s literally as though a large percentage of people just ended up, after graduating from Harvard and Yale, working for casinos in Vegas instead of startups in the Valley or auto companies or anywhere else.

But the crisis in the real economy is a slow, long decline. The immediate crisis is a blowup in the fantasy economy, the financial gambling economy. If we hadn’t had such massive deregulation we would have had more money and talent going into the real economy, and we would also not have this current crisis. What I think we need to do is dismantle and outlaw through regulation much of the fantasy economy, encourage and support investment in the real economy (including venture capital), and at the same time find a way to defuse the bomb that the fantasy economy has become without blowing up the real economy. My view is it would be better, if possible, to do this by trying to gradually neutralize and unwind the fantasy economy (get rid of the credit default swaps and get the CDOs off the balance sheets of the banks, etc.) without causing the real economy to come to a halt in the process. Maybe that isn’t possible, but given that the bubble is in an abstract economy I don’t see why in principle it isn’t possible.

If we make the fantasy economy far less large through regulation and by making many synthetic instruments illegal, then it seems to me the natural result will be the gradual recovery of the real economy, because resources will flow to the real economy by default.

permalink | 1 comment

April 14th, 2009

Like a lot of you, I’ve been discussing the economy with quite a few people, and I wanted to blog my thoughts on it here.

First of all, I tend to think that the efforts the Administration has put into place so far to deal with the financial crisis may well be insufficient, as many have argued. However I do not believe their approach is a mistake, at least as a first step, for a number of reasons.

Quite a few people have argued that we ought to force many of the big banks into FDIC receivership or some other form of nationalization as soon as possible, in order to clean them up and sell them back to private investors, so they can begin lending again. The argument that Geithner has been making is that they don’t want to do this except as a last resort, because the resulting panic might well destabilize the global economy at just the wrong moment. There’s a lot of anger out there at the banks, and at bankers, most of it quite justifiable. Many people are incensed at the idea that bankers are getting bailouts while the rest of us out here are dealing with an economic debacle.

First of all, it seems to me that Geithner is a bit too close to Wall Street and has made some politically unwise recommendations. However, I do believe that he, and Obama, are motivated by trying to stabilize the economy. I think they really believe that premature bank nationalization of the largest institutions could lead to a panic that would make the Lehman Brothers panic look like a walk in the park by comparison; and furthermore I think they have good reason to think this.

But more importantly I think we’ve been looking at the wrong targets here. The problems we’re facing are not simply the result of a small number of selfish bankers. They’re due to a larger, systemic problem. Yes, executive pay in nearly every industry, particularly in financial services, is totally out of control; it’s obscene. But the reason for our current predicament is not that a bunch of evil bankers tried to fleece us all — it’s because a bunch of relatively selfish, greedy bankers tried to maximize their returns in a short-sighted way, playing by the rules as they’ve evolved over the last few decades of excessive deregulation.

The idea that bad things happen just because some bad people screwed things up is rather naive, in my view. If we focus on that, we might get rid of one batch of bad guys but just have another gang come in to take their place. It’s a kind of Hollywood notion, that there are good guys and bad guys, and bad things happen just because of the bad guys. I think that’s just not reality.

Sure, the worst management teams ought to be replaced; the worst boards should be replaced. But if you’re relying on some “better” bankers coming in and saving us, that’s going to be a long wait.

We need to focus not so much on who’s playing the game but on the rules of the game itself. We need to roll back a lot of the imprudent deregulation since Reagan and we need to come up with new, better regulations for the future. The changes we need to make had better work whether or not we have good guys or bad guys in charge of the banks. Relying on good guys to do the right thing is clearly not workable. Sure, I agree that many bankers were selfish, irresponsible, greedy, and on and on … but that was inevitable, given the rush to deregulation we’ve seen. The system is what made it possible for these guys to operate in the way they have. Just punishing the evildoers here won’t do nearly as much as changing the game.

Why not nationalize right now, fire the boards, etc.? Well, I think Geithner is right to go slow with that. First find out with some confidence which banks are insolvent. If we have to nationalize some of them or force them into receivership, we ought to know which ones really need that and which do not, so we can avoid sowing panic in the markets. If the government forces Citigroup into receivership but there’s uncertainty about which bank is next, a panic could well ensue, forcing all of us to pay a heavy price. Instead, let’s start to try to get some pricing on these CDOs via Geithner’s public-private partnership and then see where we are. The key thing is whatever intervention is necessary ought to happen when we have some clarity about the financial condition of these institutions, so panic can be averted. I’m all for punishing the bad guys but I’d rather not do it by burning the city down at the same time. Let’s put out the fire first THEN figure out how to rebuild so we’re not as vulnerable next time.

permalink | 0 comments

March 17th, 2009

Check out the events coming up at the Synthetic Zero art space…

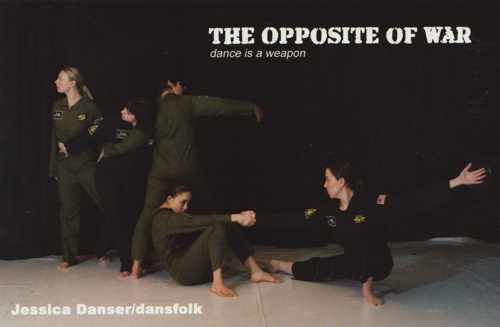

Sunday, March 22nd, 6:30pm - Jessica Danser/dansfolk presents:

Thursday, March 26th, 7pm - Portland writer, performer, and

interdisciplinary artist Tiffany Lee Brown brings the Easter Island

Project: Participation Tour to the Synthetic Zero Art Space:

Attendees are invited to bring art- and music-making gear. And she’d

“LUV it if you wanted to help document the gathering — bring video

cameras, recording devices, cameras, etc. of any quality or lack

thereof.”

Preview on Wednesday, April 1, 2009 6pm - 9pm, presentations on Saturday, April 4, 5pm - Stranger Than Fiction

Presentations and work shared by Yasmine Alwan, A.S. Bessa, Ethan Ham, Jane Hsu, and Angie Waller, curated by Laura Napier.

permalink | 0 comments

March 15th, 2009

A post for physics geeks: I’ve suspected for a long time that the long-awaited “God Particle”, the Higgs boson, which, according to the Standard Model of particle physics is the origin of the mass of particles — may well not exist. Why? It’s nearly entirely handwaving, but it comes from my ideas about the nature of the measurement problem in quantum mechanics. That is to say … Jonathan Tash and I speculated a number of years ago that the solution to the preferred basis problem of the Everett interpretation of quantum mechanics may well be that it is only in the basis that we happen to observe that you can have perception or awareness needed for what we call life; that is to say, if perception depends on feedback loops a la Gregory Bateson, those feedback loops would have to be able to “close”. Our hypothesis was that the apparent structure of spacetime itself was/is induced by these feedback loops (on some sort of underlying substrate that was itself not necessarily local in structure and which did not have a spacetime structure in particular.) However, if spacetime is induced by feedback loops, but, according to Einstein, one can interpret gravity as a bending of spacetime, then perhaps there is some relationship between these perceptual feedback loops and gravity (again, this is just my personal speculation and it is nothing more than handwaving, as I said, at this point). If, somehow, gravity itself is related to the nature of closed feedback loops, then it may be that what we call mass has to do with global factors rather than created by a Higgs field. However, I haven’t analyzed it further than this; it’s just an intuition, and a very vague one at that. But, let’s just say I’m not entirely surprised that they haven’t found the Higgs boson yet; if they do find it, I suppose I’d be slightly disappointed (but again, since I haven’t done the analysis I’m not really sure if or whether it would really affect the more fundamental ideas Jonathan and I have bandied about.) If the Higgs doesn’t exist, of course, it means there’s something fundamentally missing from the Standard Model — and I think it could be something along the lines of these feedback loops inducing spacetime. Who knows, however, it’s all just speculation (update: Jonathan wrote me just now to say he shares this intuition).

permalink | 1 comment

March 13th, 2009

I wanted to say something about the recent Jon Stewart/Jim Cramer face-off. I have to say, I thought this was one of the most powerful and to-the-point shows I’ve seen in a long time.

What Jon called Cramer and CNBC out on was not just being wrong sometimes, it was failing to do journalism. Cramer’s show is like the Daily Show in that it’s entertaining, but it’s not the Daily Show in that Cramer does not do his homework. It’s mostly him up spouting off the top of his head, not doing research, making calls based on his gut. He’s a smart guy but Jon rightly called him out on failing to use his experience and smarts and do the hard work that is incumbent upon him in his role on his show. Jon is saying: fucking take your job seriously. He has some moral authority here since it’s damn obvious the Daily Show staff does THEIR research, far better than the vast majority of real news shows out there. Yet, people with real financial knowledge and experience are up there spouting things off the top of their heads — yet he and his Daily Show writers, who he acknowledges are mainly entertainers — are out there trying to figure it all out, as best they can, without that background and expertise.

He called Cramer out not just for being wrong, but for being lazy. For not doing his job, for not taking his job seriously. And, quite frankly, I think Cramer listened. I think he actually got his point across. This wasn’t just a takedown of Cramer: it was a schooling of Cramer, and maybe a schooling of CNBC. Jon’s essentially saying: do your jobs, fuckers. If you’re going to sell yourself as a serious network covering financial news, well then, be a serious network covering financial news.

permalink | 1 comment

February 24th, 2009

Please come to my next synthetic zero event; we’ll be having a dance/music improvisational performance, many experimental videos, and visual art!

permalink | 0 comments

February 9th, 2009

From Melody Owen (one of my favorite artists): disappearing book.

permalink | 0 comments

February 2nd, 2009

On the Hardcore Dharma weblog, Julia Jonas (aka tinderfoot) writes:

Reading ZMBM I came to the conclusion that the problem is not that you think meditation is going to be good for you, improve you as a person, an artist, a lover a friend. The problem is that in order to see the illusory nature of our beliefs, its essential to let go of these ideas of improvement. I know that’s what Suzuki Roshi is saying, but it made sense to me, for the first time again, this week. Going into meditation in order for it to calm me down pits myself against myself. Going into meditation accepting the momentary, flawed state of my mind and reality and not try to change it, to rather simply be curious about it, allows me to be in the present moment.

It’s a really difficult koan. On the one hand, it seems the purpose of practice is to attain enlightenment, to be free from the cycles of karma, to attain liberation. That’s one story.

Yet, the Heart Sutra says: “There is no suffering, no origin of suffering, no cessation of suffering, and no path. There is no wisdom and no attainment. Because there is nothing to be attained, the Bodhisattva relies on prajnaparamita, and has no mental obstructions.”

Of course, the very ones who proclaim the teachings of “no attainment” are people who themselves have done quite a bit of practice, so is there a contradiction here?

Not at all. That’s the koan.

My primary meditation teacher, Steven Tainer, talks about this a great deal. His way of speaking of it is simple: of course, at first, we are so inured to the “goal oriented” mind that that’s all we have to work with (seemingly). So, if we need some sort of idea of a goal to practice, that may be unavoidable.

But to the extent we hold onto the idea of a goal, of a result we are trying to attain … practice is obstructed. That’s not only Suzuki and Trungpa’s view, it’s also Steven’s view (and the view of many teachers). I have to say that in my many years of practice, I’ve come to realize that these great teachers were, as one might imagine, and hope, entirely correct.

But that doesn’t make it easy to understand what the hell they’re talking about.

Ultimately an intellectual understanding of this is not entirely possible, though I do believe it’s very important to try to understand it intellectually as best we can, because a purely “experiential” understanding, as some put it, can be dislodged without careful study. That’s an important point worth noting.

One view I have of this is something along these lines; it’s a picture, so to speak. Which is to say it is inaccurate, as all pictures are.

But essentially: if we realize that who we think we are (the so-called “self”) is really just a sort of phantom, a kind of tiny fragment of a much larger landscape of who we really are, in a deeper sense, then to think in terms of a “goal” is usually to think in terms of the “self” accomplishing or “doing” it. Yet the whole point of all this is to realize that this little “self” is not really who we are, we are not limited to that, we’re much bigger than that.

Thinking in terms of a goal is thinking in terms of a small self doing or accomplishing the goal.

Practice is not a method for the self to accomplish enlightenment. Such a project is impossible. The “self” cannot accomplish this.

Practice is more like a posture, a gesture, a way of aligning ourselves with the radical reality of our true selves, which is vast. Big Mind, so to speak. By making this gesture we allow our larger reality a chance to come forward on its own. It’s always there, but we ignore it, we crowd it out. Even though we ignore it, it is still there, still functioning. We don’t have to produce it. We don’t have to “achieve” it or become it. We are always already Big Mind. To the extent we can relax our desire to “achieve” enlightenment, we make it easier for us to be who and what we already are, to relax into that larger being, to let it be what it already is.

Practice is important, even perhaps essential for most people; but it is not an action undertaken by the self to effect a result. It is more like a way of aligning ourselves with the resonance of the universe, which is already vibrating whether we feel or hear it or not. By doing so we don’t cause our self to achieve a goal, but we may allow our Big Mind or Being to come forward more visibly into our conscious life and awareness. If we have a job it might be to get out of its way; but we don’t even have to do that, really; as it is always there whether we get out of its way or not.

permalink | 10 comments

January 30th, 2009

Susanna was telling me today that she was really struck by how much of a shift it is that Obama is a president from or close to our generation. I’ve been remarking on that, too; friends of mine talk about Obama as though he were someone they knew personally. I notice people wondering what it “must be like” for Obama to be doing this or that Presidential activity for the first time; and I have to admit, I have the same thoughts. Oh, it must be cool to live right upstairs from where you work, or what must it be like to sit in the Oval Office? I don’t remember thinking this about any previous President.

But there’s more to this change, I think, than just being able to relate to the President — it’s a shift to a new, post-partisan, pragmatic way of thinking about the world. To some, this may remind them of the DNC’s style of triangulation politics — but I believe it’s actually a much more interesting, radical change in policy thinking, one which is long overdue, and one which, I believe, does represent a current in thinking in our generation which is less ideological but not merely an averaging of opinions from the left and the right. To the contrary, the idea is to recognize that any given principle is just one aspect of a multidimensional reality that must be respected in all its complexity. Rather than attempt to achieve ideological purity (the market is infallible! the market is the root of all evil!), one looks at the situation and sees context — in certain contexts (trying to find a reasonable short-term price equilibrium) the market is better, faster, more flexible than the government, yet in other contexts (looking out for longer-term concerns, the environment, damping down market bubbles, looking out for fraud and abuse), the government is indispensable. It’s not a politics of just one side or the other, nor is it simply a bland averaging of political views — rather, it’s a recognition that the political spectrum encodes principles which all must be taken into account, depending on context. For example, on the use of the military: yes, we can and should fight to defend ourselves against those who are trying to kill us; but at the same time, we should do so while remaining true to our principles, without torture, while also attempting to negotiate whenever possible.

It all sounds so obvious, and so sensible, and most of my peers think this way naturally. Yet for so long this sort of multifaceted, principled, but also sophisticated thinking has been absent from mainstream political discourse; even those who were themselves quite intelligent (say, Bill Clinton) found it necessary to dumb down their public image and message. Obama does this much less than any national politician we’ve seen in a long time; and he does more than this, he tried to elevate the discourse whenever he can, through rousing rhetoric which is nevertheless frequently far more sophisticated than we’ve been exposed to in recent decades.

permalink | 0 comments

January 25th, 2009

Words cannot express the anger I feel about this story:

Pope Benedict XVI, reaching out to the far-right of the Roman Catholic Church, revoked the excommunications of four schismatic bishops on Saturday, including one whose comments denying the Holocaust have provoked outrage.

You know, I have great respect for the contemplative tradition in most religions, and the Catholic Church is no exception; they’ve produced or been associated with great mystics, both historically and recently, including the wonderful Thomas Merton, the keenly insightful and brilliant Simone Weil, and many others in their long history. But one has to wonder, at times, if this is because of or in spite of the Church itself. There are so many things wrong with the Catholic Church as an institution that it’s hard to know where to begin; perusing the Vatican website is an exercise in reading some of the worst, most ill-informed, and clueless theological and spiritual writings ever conceived by man. Time and again they replace true contemplative insight (which they supposedly revere in saints such as Teresa of Avila, though I can only conclude the vast majority of the officials in the Church have no idea, literally no concept whatsoever, what many of the saints they supposedly revere experienced or understood) with theology which substitutes muddled dogmatic thinking and outright horrific error for true contemplative insight. The inference one can draw from this is they believe that following rules and subscribing to “beliefs” without any basis can be a stand in for meditation, contemplation, and surrender, something which is not only wrong but horribly misguided and harmful to the world. Of course, they’re not alone among the world religions in making this mistake, but they have a certain arrogance, a false majesty projected by their feudal institutions and hierarchy, all the way up to the office of the Pope, which has all sorts of royal pomp surrounding it, even though the current occupant of that chair is perhaps one of the worst in a long time, though the office has a famously dark past, people who have either presided over or actively encouraged corruption. As an institution, its failings have not, as we all know, only been restricted to history, but they’ve continued even into modern times.

I was discussing all of this with a friend of mine a while ago, and she pointed out that, “at least they excommunicated the Holocaust denier” — and I had to give her that. Though the Church as an institution (and note that I am describing the acts of the institution, not the religion per se, though the religion makes great efforts to imply the two are one and the same, which is itself a crime) has had a very dark ancient as well as recent past, there have been positive things too — in addition to many blameless saints and mystics, who I referenced above, there were institutional advances, such as Vatican II. But with this move, Ratzinger has made a gesture which symbolically validates not only that Holocaust denier (in itself the worst aspect of this move) but the worst aspects of intolerance and dogma.

Dogma is the bane of spiritual life. It is not only a risk to spirituality and contemplation in any religion — it is the origin of religious and ethnic hatred, wars, oppression, and death. Sure, one has to live with a certain degree of dogma in any culture and society — it’s a natural and inevitable response, an attempt to replace the mystery and majesty of the universe with something people can grasp more concretely: bureaucracy. I don’t begrudge those who decide they must, for their own reasons, subscribe to some sort of dogma, but the arrogance of someone like Ratzinger, who is clearly someone who lacks any deep spiritual insight whatever, in not only promoting but elevating through the dint of his office, under the color of authority and the gilded majesty of the papal seat, in pushing for the rehabilitation of the least spiritually aware, the most damaging ideas, including but not limited to Holocaust denial… it’s simply disgusting. There are few things I get truly angry about, but abuse of authority is one of them. Ratzinger exhibits an unearned contempt for true understanding, he is using the position of his office to promote a narrow, rigid, and impoverished spirituality, to give it legitimacy; yet he has not earned the right. In Buddhism ignorance is a sin, but even worse is ignorance masquerading as authority and spread out over the world under its rubric … it’s hard to imagine a worse crime in terms of its long-term negative historical impact.

Meanwhile … in other awful news, the BBC has decided not to broadcast a charity appeal from notoriously controversial organizations such as Save the Children, Oxfam, and the Red Cross to aid Gaza. It’s hard to fathom such a bizarre and unconscionable refusal; they claim it is to preserve their “appearance of impartiality,” as though helping international aid organizations to relieve civilian suffering in Gaza is anything but a simple matter of human compassion. It’s one thing to want to be even-handed, but is the BBC so afraid of being critical, even indirectly, of Israel, that they cannot bring themselves to allow non-political aid organizations to advertise for help to support victims who no one, not even Israel’s supporters in this war, would argue are at fault for their own suffering?

As a meta comment: I was thinking a bit about the twin nature of my outrage for the day … on the one hand, outraged that a Holocaust denier, among others, was being rehabilitated by one of the most venal Popes in decades, if not centuries, and on the other, outraged that the BBC would attempt to thwart humanitarian organizations from helping victims of a military onslaught by Israel. My outrage is on both sides of the political divide when it comes to Israel and Jewish history, at least, but then again I have always found that the things I find the most disgusting, the most horrific, can be found on every side of nearly every political, ethinic, cultural, and religious boundary. Victims and the victimized can be found everywhere, committed by every group. Yet people tend to be rather one-sided in their ethical concern; they may rage against the “enemy” but not themselves, or sometimes vice-versa; but why not resist, loudly and strongly, crimes whether they’re committed by your side or the other side … crimes are crimes regardless of what side you’re on. I don’t believe, that at any given point in history, of course, that crimes are necessarily equally distributed — integrated over the long haul, however, one can find even the most virtuous nations, organizations, and individuals committing acts of thoughtlessness, oppression, all the way up to genocide and worse, and we, as human beings, ought to be prepared to see it in humans, including ourselves, regardless of where they happen to be on one side or the other of a geographical, political, ethnic, or religious boundary.

permalink | 0 comments

|

|

|